Kvennaskóli Húnvetninga was founded in 1879 in Undirfell, Vatnsdalur valley and operated for almost 100 years.

No products found for vendor

Kvennaskóli Húnvetninga was founded in 1879 in Undirfell, Vatnsdalur valley. One of the founders was the farmer and member of parliament, Björn Sigfússon. Born in 1849, he was a young man who had spend time abroad, and knew of the major advancements in educational opportunities for women and girls. He thought that women should be able to educate themselves, not only the sons of well-to-do farmers, as was the custom in Iceland at the time. Many of his contemporaries thought the same. During the 1870s, three other women's colleges were founded in Iceland: Kvennaskólinn í Reykjavík (1874), Laugalandsskóli, and Kvennaskóli Skagfirðinga (1877).

Ytri-Ey

At first, Kvennaskóli Húnvetninga was funded by the district and with donations. During the first year, lessons were held at the home of pastor Hjörleifur Einarsson in Undirfell. He taught theory, his niece Björg Schou practical subjects. The students were five girls, who stayed at the school for eight weeks at a time, three times over the fall and winter months. The following year, Kvennaskóli moved to Lækjarmót in Víðidalur valley, where Elín Briem became the director, and four years later to Ytri-Ey (between Blönduós and Skagaströnd), where the school was located for 18 years.

In 1880, the Húnavatnssýsla and Skagafjörður districts took over the management of the school, supported by grants from the state. Statutes were written, rules and regulations introduced. When the school moved to Ytri-Ey, the school year started on October 1st and ended on May 15, divided into two teaching periods. There was a first and second grade, as well as a handicrafts department.

Exams were held in all the subjects, with external examiners coming in. At the house in Ytri-Ey, there was space for 20 women, including teachers. Amongst the subjects taught were calligraphy, maths, geography, history, Danish, song, tailoring, embroidery, and cooking. At first, students came from the surrounding districts, but soon there were applications from students all around the country.

Textbooks

Teaching calligraphy, head of school Elín Briem was using a special kind of imported paper and style ("koparstunga"). The Ytri-Ey students were known for their beautiful handwriting. In 1888, Elín Briem wrote and published Kvennafræðarann, a handbook on cooking, food storage, and handicrafts, including the tailoring of clothes for men and women. The first edition, 3000 copies, was quickly sold out, and the book - now considered a classic in Iceland - was reprinted three times.

In 1900, the decision was made to move the school from Ytri-Ey to nearby Blönduós. Skagafjörður municipality withdraw from participation regarding the management of the school. Carpenter Snorri Jónsson from Akureyri was hired to build the school, and on October 1st, 1901, 30 students attended the first lessons in the new house.

The school burns

On February 11th, 1911, Kvennaskólinn burned down in a fire. Much was lost, but all lives were saved, as well as much of the food stored in sheds outside. This made it possible to continue teaching, with classes being held in houses Tilraun, Templarahús, and Möllershús in Blönduós, and students staying in different homes nearby. The new school house, planned by master builder Einar Erlendsson from Reykjavík, was built in record time and opened in the autumn of 1912 in the same location. It featured modern amenities, such as bathrooms, toilets and running water, but no electricity until 1927.

The school's finances were fragile at times, and providing resources a constant struggle for the participating districts. During a particularly difficult period, the winter of 1918 - 1919, the school was forced to close, also due to the lack of fuel and heating materials. But people were protective of the activities of Kvennaskóli, which was very professionally managed and had a great reputation, and pleased with its success as an educational institution. The school reopened, and in 1923 - 24 was changed into a so-called Húsmæðraskóli, a 9 month program with a focus on home economics and practical subjects such as cooking and sewing. Subjects also included Icelandic, bookkeeping, Danish, nutrition, and health education. This was to remain the direction until 1970, although there were a number of changes regarding the curriculum over the years. In the 1940s, for example, Danish and maths were no longer taught, but textile chemistry, "product knowledge" (vöruþekking), and home bookkeeping added.

In 1952, the school building itself was changed. An extension was built - including an apartment for the head of school and dining room - the kitchen and bakery improved, and new furniture bought. Lessons were paused until renovations were completed, and finally resumed in January 1954. Hulda Stefánsdóttir, who led the school from 1932 - 37, was hired as the director for a second time.

From 1970 onwards, there were significant changes in the educational landscape in Iceland, and the interest in home economic schools dwindled. This also affected Kvennaskólinn in Blönduós, despite much effort made. During the 1970s, two teacher's houses were built next to the main building, storage space and work rooms added, as well as a large classroom with balconies on the second floor. Students were given the option of staying only half the school year, and taking shorter classes in e.g. weaving and cooking.

Kvennaskóli started collaborating with the elementary school in Blönduós, and housing older students about to take their final exams. Locals remained supportive of the school, and many - 400 in all - participated in the various classes offered to them. But in the autumn of 1978, the decision was made to close the school once and for all. Other home economic schools also closed at the time.

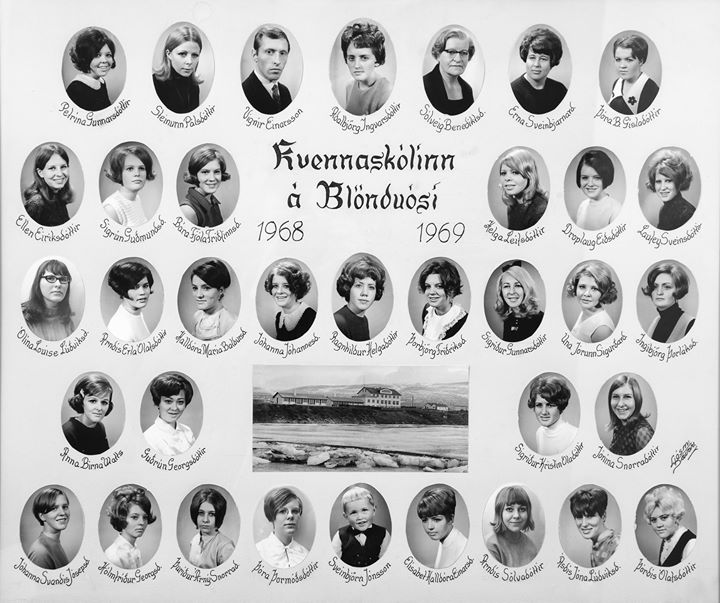

All in all, 2700 women and girls were educated at Kvennaskólinn during the 99 years it was operated. The many other students attending individual workshops and classes are not included in this number. Most students came from the surrounding districts, Húnavatnssýslur and Skagafjórður, as well as the districts near Akureyri and Strandir on Húnaflói Bay. During the final years, many students came from the capital city area.

Kvennaskólinn was a source of much activity and an integral part of Blönduós and the region. The women leaving the school oftentimes stayed in the region, marrying local men, and bringing their knowledge into their new homes. Many were sad to see the school go. The neighborhood seemed lifeless and not as colourful when Kvennaskólinn closed.

Aðalbjörg Ingvarsdóttir.